How does the social environment influence WASH practices?

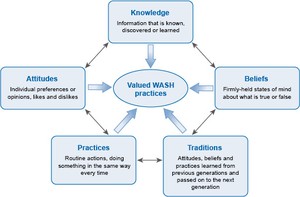

The building blocks of our behaviour lie in our knowledge, practices, attitudes, beliefs and traditions, all of which contribute to the social environment. Figure 13.2 summarises the interactions between these invisible aspects of the inner personal world of every individual and their community, and shows that they all influence whether good water, sanitation and hygiene practices are adopted.

Figure 13.2 Diagram summarising the interaction between knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, practices and traditions in a community and their influence on valued WASH practices.

We have called the behaviours at the centre of Figure 13.2 ‘valued WASH practices’ to indicate that they are actions that a community values and approves. Individuals who are observed doing these actions (for example, washing their hands before eating) gain credit from others in the community because they are behaving in these valued ways. An example of a behaviour that is valued in rural Ethiopia is debo, the practice of neighbours working together to harvest the crops from each farm in turn.

Notice that each part of Figure 13.2 is interacting with all the other parts to influence valued WASH behaviours. The main message of the diagram is that you must consider all these aspects in the social environment of your community if you want to be successful in replacing unhealthy or environmentally damaging behaviours by valued WASH practices. We begin by considering the limitations of knowledge to bring about behaviour change from unhealthy to good WASH practices.

Knowledge of WASH practices is not enough to change behaviour

Knowledge can be defined as all the information we have learned and synthesised during our growth and development.

We assume you know that people who drink dirty water may get sick as a result because harmful bacteria live in the water. Think for a moment about how you acquired this knowledge?

You may have been told not to drink dirty water by your parents; or perhaps you learned about bacteria at school; or maybe the Health Extension Worker made a poster about only drinking clean water to avoid getting diarrhoea; you could have heard about it on the radio, or learned from your own experience if you drank dirty water as a child and developed diarrhoea afterwards.

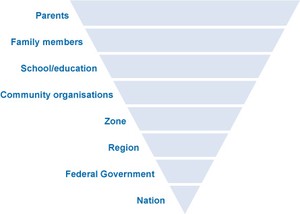

Figure 13.3 summarises the ‘upside-down pyramid’ of sources of knowledge acquired during a lifetime.

Figure 13.3 Diagram representing the different levels of influence on a person’s knowledge.

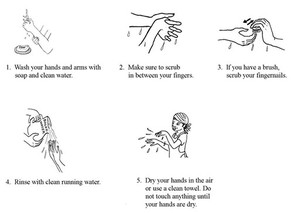

Education is a key factor in improving the knowledge of WASH issues in a community. Learning about hygiene and sanitation in school is a particularly important driver of behaviour change. The Ethiopian government has a strong commitment that all children should attend school. If children learn the right way from a young age, they will keep good WASH practices throughout their lives. For example, they can be taught the correct way to wash their hands at critical times, that is, before and after preparing food or eating, and after urinating, defecating or cleaning a child’s bottom (Figure 13.4).

Figure 13.4 Correct handwashing takes about one minute.

However, health education programmes are often unable to achieve behaviour change simply by giving adults knowledge of the health risks of poor hygiene or why they should not pollute the physical environment with waste. Even if people are given accurate information about what causes diarrhoea, this knowledge is generally not enough to persuade them to change poor hygiene and sanitation practices, their routine actions, doing something in the same way every time. For example, people whose routine practice is to defecate in the open every day are unlikely to change their behaviour simply because they have been given new knowledge about the risks to their health and the environment.

Attitudes, beliefs and traditions influence WASH practices

There are several reasons why unhealthy WASH practices persist, even if people have been given good information to help them change for the better. If you look again at Figure 13.2, you can see we have put ‘attitudes’ and ‘beliefs’ on either side of ‘valued WASH practices’. Attitudes are individual preferences or opinions about what a person likes or dislikes. Beliefs are firmly held states of mind about what is true or false. One reason for the persistence of bad WASH practices, even when correct knowledge is available, is that people have attitudes and beliefs that make them ignore the facts.

Can you suggest an attitude and a belief that people might express about not using a latrine even when there is one nearby?

Here are our suggestions, but you may have given other good answers:

- Attitudes against using latrines: ‘I dislike using latrines because they smell bad’; or ‘I prefer to empty my bowels in the open because the bad smell is blown away by the fresh air’.

- Beliefs against using latrines: ‘The bad odour collects in the latrine and causes disease if you breathe it into your body’; or ‘It is safer to defecate in the open because there are evil influences in latrines’.

Good WASH practices at community level also include handwashing, accessing clean drinking water, and keeping the physical environment clean and free from waste. Sustaining these practices builds our health, improves our lifestyle and helps us all to live longer. But first, negative attitudes and beliefs must be overcome and replaced with valued behaviours. For example, handwashing with soap before eating is not practised by everyone in Ethiopia, even though it prevents transmission of infection from dirty hands to the mouth. (Figure 13.5).

Figure 13.5 Handwashing with soap before eating is a valued WASH practice.

The example we gave earlier of debo – the valued practice in rural communities of neighbours helping to harvest crops from each other’s fields – can also be termed a tradition, a behaviour that is learned from previous generations and passed on to the next generation. Some traditions, like debo, bring positive benefits to the community and also to the environment. But some traditions expose people and the environment to possible harm.

Open defecation is a tradition in communities like the one we described in Case Study 13.1. Can you recall the tradition mentioned by some of the people he spoke to?

They told him that they continued to defecate in the open because their ‘ancestors never used latrines’. Behaviour that was accepted by the ancestors has become a tradition that people in this community pass on to their children.

Tradition is one reason why, according to the report of the Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation in Ethiopia (JMP, 2014), about 37% of Ethiopians were still practising open defecation in 2012.

Traditions are very difficult to change because everyone in a community believes it is the right way to behave. Individuals who challenge the tradition are likely to meet opposition from the majority who want to go on doing things in the old way. If open defecation or not washing the hands at critical times is considered normal and traditional in a community, it will take time and effort to persuade people that using a latrine (Figure 13.6) or handwashing with soap are valued practices that benefit the whole community and also protect the environment.

Figure 13.6 It takes time and effort to convince people that building a covered pit latrine like this one will benefit their family’s health and improve the local environment