Microenterprises

A microenterprise can be defined as a small business that employs fewer than ten people and is started with a small amount of capital. Water supply is an area in which microenterprises operate in a number of different ways, as you will discover in this section.

Selling water at public taps

Public taps (Figure 15.1) are one way of distributing water. The water is sold to people by volume, and customers come to the public tap with water containers. Although many of the public taps are owned and run by the public utility, some are microenterprises: the water is bought from the water utility by the tap attendant and then sold on to consumers at a higher price. A survey of public taps in Addis Ababa (Howard, 2005) found that water was being sold at a price up to eight times the cost of buying directly from the water utility! Public taps are open for only a few hours each day, which can sometimes result in long queues.

Figure 15.1 A public water point in Addis Ababa.

Selling water using tankers

Private sellers also supply water through the use of water tankers (Figure 15.2) licensed by the government. This happens in areas not served by a piped water distribution system. The tanker usually has a capacity of 20,000litres and the water is pumped into water storage tanks at the households, which usually have a capacity of about 3000 litres.

Figure 15.2 A water tanker in Denan, Ogaden.

Water vendors

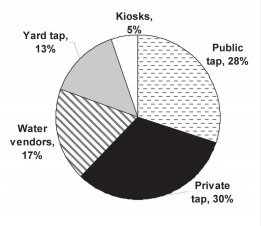

In a survey of three poor areas of Addis Ababa (Sharma and Bereket, 2008), it was found that 17% of the respondents (Figure 15.3) obtained their water from water vendors who had originally purchased the water from the public water utility (the Addis Ababa Water and Sewerage Authority). The water vendors in cities are usually people who have private taps in their homes or yards and who sell water from these. The price at which the vendors sold the water to the end users was again about eight times the price paid for the water, corroborating the findings of Howard (2005). Sharma and Bereket found in their survey that most people would have preferred to have their own private tap but the high initial cost of a private connection was prohibitive. If this could be paid in small instalments, 90% of those keen to acquire a private tap would take up the option. In Kombolcha, in Amhara Region it is possible to do this, with the set-up cost being paid in four instalments. There is scope for a private–public partnership here, with private companies providing the administrative arrangements to collect the instalments.

Figure 15.3 Means of obtaining water in three poor areas of Addis Ababa in 2008. (Sharma and Bereket, 2008)

There are also water vendors who sell water from horse-drawn or donkey-drawn carts (Figure 15.4).

Figure 15.4 A water vendor selling from a donkey-drawn cart in Ethiopia.

Selling water at kiosks

Sharma and Bereket (2008) found that the price of the water at kiosks (Figure 15.5, which were described in Study Session 7) was about three times the cost of water from the water utility. Water kiosks are common in the countries of sub-Saharan Africa, and water is brought from the kiosk owner’s home to the kiosk and sold. Alternatively, if the kiosk is near the home of the owner, a hose connection to the house tap enables water to be sold direct. In a typical day a kiosk can serve 500–3000 people bringing their own water containers.

Figure 15.5 A water kiosk in Afto, Ethiopia.

Selling water-related services

As part of the water industry, several microenterprises have emerged to supply plumbing services such as fixing leaks, extending pipelines around a house or compound, and selling and installing plumbing systems (such as tanks, pipes, latrines, WCs, etc.) (Figure 15.6).

Figure 15.6 A toilet shop in Addis Ababa.