The components of a Water Safety Plan

Water Safety Plans can vary in complexity depending on the scale and type of water supply system being considered. In general, there are ten components in a Water Safety Plan (Figure 8.1).

Figure 8.1 The steps in a Water Safety Plan.

Although the stages depicted in Figure 8.1 are sequential (i.e. you do them one after another in a sequence), they can be undertaken by teams of people working in parallel, looking at different aspects of water supply. For instance, there could be teams looking separately at the catchment, treatment plant and distribution system. We will now look at each of the steps in turn.

Assemble a team of experts

In order to draw up a Water Safety Plan, full information about the water supply system, from the catchment to the taps of consumers, is required. This will include details of the catchment (such as possible sources of contamination), the abstraction point, the pipes (sizes, construction materials, etc.), the units at the treatment plant, the distribution system (piping material, possible weak spots, etc.). To compile this information, a team of experts is required.

The expert team (Figure 8.2) should include not just technical experts but local people because they will be most knowledgeable about what is actually on the ground. Local people may include farmers and forestry workers, landowners, and representatives from industry, other utilities and local government, and consumers. Collectively the team should have the skills required to identify hazards and determine how the associated risks can be controlled. The definitions of hazards and risks are given in Box 8.1, where the difference between them is explained.

The support of senior management is crucial for the formulation and implementation of a Water Safety Plan, because changes in working practices may be needed, as well as new systems (costing money) for the control of risks. The finance and time requirements for preparing the Water Safety Plan will need to be approved by senior management who are the supervisors and decision makers responsible for implementing any actions that may be required. Depending on the context, senior management could be the Town Water Board or the Woreda WASH Team, for example.

Figure 8.2 The team of experts should have a range of knowledge and skills.

Box 8.1 Hazards and risks

Identifying hazards and assessing risks are important aspects of preparing a Water Safety Plan. A hazard is something that is known to cause harm. Bartram et al. (2009) define a hazard as ‘a physical, biological, chemical or radiological agent that can cause harm to public health’. Risk is the likelihood or probability of the hazard occurring and the magnitude of the resulting effects.

Here is a simple example. If you climb a ladder, you know there is a chance you could fall off and be injured, although it is unlikely. The ladder is the hazard and the likelihood of your falling off and hurting yourself is the risk. Risk assessment is about evaluating a situation to determine how likely it is that the potential harm from the hazard will happen.

Describe the water supply system

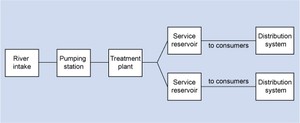

The water supply system (Figure 8.3(a)) has to be fully described. This will allow hazards to be identified, and risks to be assessed and managed. In many cases, this information will be available and will only need reviewing to ensure that it is up to date, and checked for accuracy through site visits. A flow diagram that shows all the major elements of the water supply system (Figure 8.3(b)) should be drawn.

Figure 8.3(a) A water supply system.

Figure 8.3(b) The elements of a water supply system.

In the case of springs and wells, it is important to know where the rainfall is percolating into the ground to replenish the groundwater. This will highlight the area where protective measures (such as restrictions on, say, fertiliser or pesticide use) are needed so that contaminants are not carried by the rainwater into the groundwater.

Identify the hazards and hazardous events

It is important to identify the potential hazards at each stage of the water supply process (see Box 8.1). Hazardous events in this context are defined as events that can introduce hazards into the water supply. A hazardous event can also be considered a source of a hazard. Table 8.1 gives examples of hazardous events and hazards that can affect different parts of a water supply system.

Table 8.1 Possible hazards in a water supply system. (Adapted from Bartram et al., 2009)

| Hazardous event (source of hazard) | Associated hazard | Component of water supply system affected |

| Agriculture | Microbial contamination from animal excreta, pesticides, nitrates from fertiliser use | Catchment |

| Mining | Chemical contamination | Catchment |

| Interruption of power supply | Interruption of treatment | Treatment |

| Disruption of disinfection due to lack of disinfectant supply | Unsafe water goes to consumers | Treatment |

| Mains burst | Contaminants getting into pipeline | Distribution network |

| Illegal connections | Contamination of water supply by back-siphonage | Distribution network |

Site visits are an effective way of ensuring all possibilities are covered (Figure 8.4). It is important to speak to the people who work at the locations concerned as they will have local knowledge that may not necessarily be in the paperwork related to the facility.

Figure 8.4 Testing water quality is an important part of hazard assessment.

Carry out a risk assessment and prioritise the risks

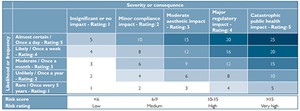

Risk is the likelihood of a hazard affecting the water supply system. A risk assessment can be carried out if the risk and the severity of the associated hazard are known. A method of undertaking a risk assessment quantitatively is to use a risk matrix as shown in Figure 8.5 (Bartram et al, 2009). The severity of the impact of a hazard and its likelihood can be multiplied together to arrive at a figure that indicates its risk score. The risk rating will be determined by this risk score, as shown at the bottom of Figure 8.5.

Figure 8.5 A risk matrix for risk assessment.

To illustrate this application of a risk matrix, suppose you wanted to carry out a risk assessment for the case where a treatment plant runs out of chlorine disinfectant (Figure 8.6). In a properly managed plant, with a system of stock control in place, such an occurrence may be rare (with a rating of 1). The public health impact of it, however, will be catastrophic (with a rating of 5). Using the matrix in Figure 8.5, you can calculate a risk score, which will be the product of 1 and 5. This risk score of 5 can then be given a risk rating. From the scale in Figure 8.5, this would be ‘low’ (being less than 6).

By repeating the exercise for other hazards and risks and comparing the risk scores, a prioritised list can be drawn up that ranks the risks in order of importance. Unfortunately, budgets are often limited and because of this many of the smaller risks are disregarded.

Figure 8.6 Drums of chlorine – essential stocks for a water treatment plant.

Identify the control measures needed for each risk

This means identifying the precautions (control measures) that need to be in place to eliminate or minimise the risks to the water supply system. So, in the example above, you would need to have a system of stock control that tells you when chlorine stocks are running low. Stock control may use some form of manual record keeping in a book or an electronic system (Figure 8.7). These have to be checked for effectiveness, as part of the Plan, and improved if necessary.

Figure 8.7 Display from an electronic stock control unit.

Define the monitoring system for each control measure

A system of regular monitoring has to be established to check that the control measures are working. Again, using the example above, someone will have to check that the records of chlorine availability in the store match what is actually present.

Prepare management procedures

A set of clear instructions to enable the whole water supply system to be operated as desired has to be in place. If there is an incident that disrupts the normal operation of the system – for instance, if a control measure fails – then a number of actions need to be followed. These should be documented in the management procedures so that they are easy to refer to and apply. The relevant management procedure will detail the remedial measure, what communications to undertake and the steps to follow in an investigation of the failure.

Do you remember the usual name for the routine instructions for operating a water treatment plant?

They are often referred to as standard operating procedures or SOPs.

Following through the example of chlorine stock, if the supply were to run out, the management procedure might suggest contacting nearby water utilities (using names and telephone numbers of contact persons who had previously been consulted) for a loan of an amount of chlorine. An alternative might be to contact supply companies that could rapidly acquire and supply the chemical (but this is likely to be at a high cost!). The population affected by the break in supply would have to be informed of the crisis, possibly by messages on local radio and television programmes. Lastly, an investigation needs to be undertaken as to how the crisis came about, and how it can be prevented from recurring.

Prepare verification programme

The verification programme is to check that all the components of the water supply system are working properly, and that water of a suitable quality and quantity is being supplied to the population, and therefore that the Water Safety Plan is working. There are three activities that together provide evidence that a Water Safety Plan is working effectively:

- compliance monitoring

- internal and external auditing of operational activities

- assessment of customer satisfaction.

In compliance monitoring, sampling and analysis of the water is undertaken to verify that the water quality standards are being met (complied with). For microbial verification, indicator organisms such as E. coli or faecal coliforms are looked for at representative points in the water supply system. In appropriate cases (say in areas with a Cryptosporidium problem), measurement of the organisms may be necessary. For chemical parameters, direct measurement is carried out, rather than the use of an indicator.

In internal and external auditing, scrutiny of the operational practice is undertaken by an auditor in person to verify that good practice is in place. As the names suggest, internal audits are undertaken by someone from within an organisation and external audits by an independent, objective auditor from outside an organisation. Auditors will, for instance, identify areas where procedures are not being followed, resources are inadequate or training is required for staff.

Assessment of customer satisfaction is the third aspect of verification and this is undertaken by personally meeting with representative consumers to obtain their feedback on the quality of the water delivered to them.

Develop supporting programmes

Supporting programmes are activities that support the development of people’s skills and knowledge in relation to delivering safe water. These mainly involve training, and research and development. To ensure that the Water Safety Plan is current, staff need to be updated on changes in the water supply system, and the revised actions they need to take in times of emergency. In the case of the chlorine supply running out, an investigation of the crisis will reveal whether staff retraining has to be conducted, or if the system for monitoring chlorine stocks needs to be modified, or indeed if both need to be done. The Water Safety Plan will have to be reviewed as a consequence.

Supplementary programmes include sessions to educate members of the public on how they can ensure that the water supply is kept safe (for example, by giving them information on how back-siphonage can contaminate the water distribution system).

Document all of the above

All the sections detailed above have to be documented so that there is an audit trail, in case any step has to be reviewed. (An audit trail is a chronological record that provides documentary evidence of the sequence of activities that led to a given decision.) Keeping clear and complete documentation enables the Plan to be reviewed periodically. This is important because changes can happen anywhere along the water supply process. New risks might arise, or more efficient and economical methods might become available to control the different risks.

In addition to regular review and updating, it is important that the Plan is reviewed and possibly modified following an incident or crisis. A post-incident review, where the incident is discussed in detail, is likely to identify areas for improvement in the operating procedures, training or communications, and these should be incorporated in a revised Water Safety Plan.

Case Study 8.1 Water Safety Plan at community level in Ethiopia

In Hentalo Wejerat woreda, in Tigray Region, Water Safety Plans were used to improve water supplies in small communities and ensure access to safe and clean water (Drop of Water, 2014).

Twelve individuals were trained as Trainers in Water Safety Planning by specialists from the World Health Organization. The training covered the principles of water safety planning, risk management for the supply of drinking water, guidance on developing Water Safety Plans, surveillance and control of small community water supplies, and safe practices in household water use. Three Water Safety Planning Teams were then established.

The three Water Safety Planning Teams were given training that focused on the impact of unsafe water, assessing environmental contaminants, operating a hygienic water point and the physical treatment of water at household level. They then applied Water Safety Plans to three water points at Lemlem Queiha, May Weyni and May Yordanos.

At Lemlem Queiha, although there was a fence at the water point, there was no gate. The area around the water point was unclean, and the water point was vulnerable to flooding. Not all the houses in the vicinity had latrines, which meant open defecation was taking place. The community had a poor awareness of good hygiene and sanitation. Jerrycans used for collecting water were unclean.

At May Weyni, the fence at the water point had been damaged by flood and had not been repaired, and there was no gate. Nearly all the residents had latrines at their homes.

At May Yordanos, the water point was found to be clean and well fenced. Water handling was hygienic both at the water point and in the residents’ homes. The houses had latrines, which meant that open defecation was eliminated. The community had a good awareness of hygiene and sanitation.

Over the one-year period of the project, with the aid of the Water Safety Planning Teams most of the residents installed latrines, and gained a good knowledge of hygiene and sanitation. The water points were kept clean, and good water-handling practice was adopted at water points and in homes. Open defecation was almost totally eliminated. Gates were installed at the water points at Lemlem Queiha and May Weyni, and the broken fence at May Weyni was repaired, to prevent contamination by animals.

In what ways does Case Study 8.1 correspond to the ten steps of Water Safety Plans described in this study session?

The actions taken in the case study correspond to the first few steps in a Water Safely Plan:

- Assembling a team of experts: twelve people were trained so that they had the expertise to undertake a Water Safety Plan.

- Description of the water supply system: details of the three water points were recorded.

- Identification of hazards: the various hazards at two of the water points (lack of gates, lack of a fence, unclean areas around water points, the susceptibility to flooding, open defecation, poor awareness of good hygiene and sanitation, unclean jerrycans) were noted.

Less well-fulfilled steps were:

- Carrying out a risk assessment: this does not appear to have been done, but it was perhaps unnecessary in the simple situation faced by the Team.

- Identification of control measures for each risk: control measures focused on addressing the hazards identified earlier. Hence, gates were installed, a fence was put up, the water points were kept clean, latrines were installed (almost totally eliminating open defecation) and information on good hygiene (covering water handling practice) and sanitation was disseminated to the residents. The issue of flooding did not seem to have been resolved.

- Defining a monitoring system for each control measure: since the residents had received information on good hygiene and sanitation, it is likely that they would endeavour to maintain good practice.

- In a small community context, preparing management procedures and a verification programme, and developing supporting programmes, are not needed.

The above was an example of the application of a Water Safety Plan but in a rural context. Hence not all the ten steps necessary in an urban situation were applicable to achieve the positive outcome.